Hidden in Plain Sight: Venetian Campi

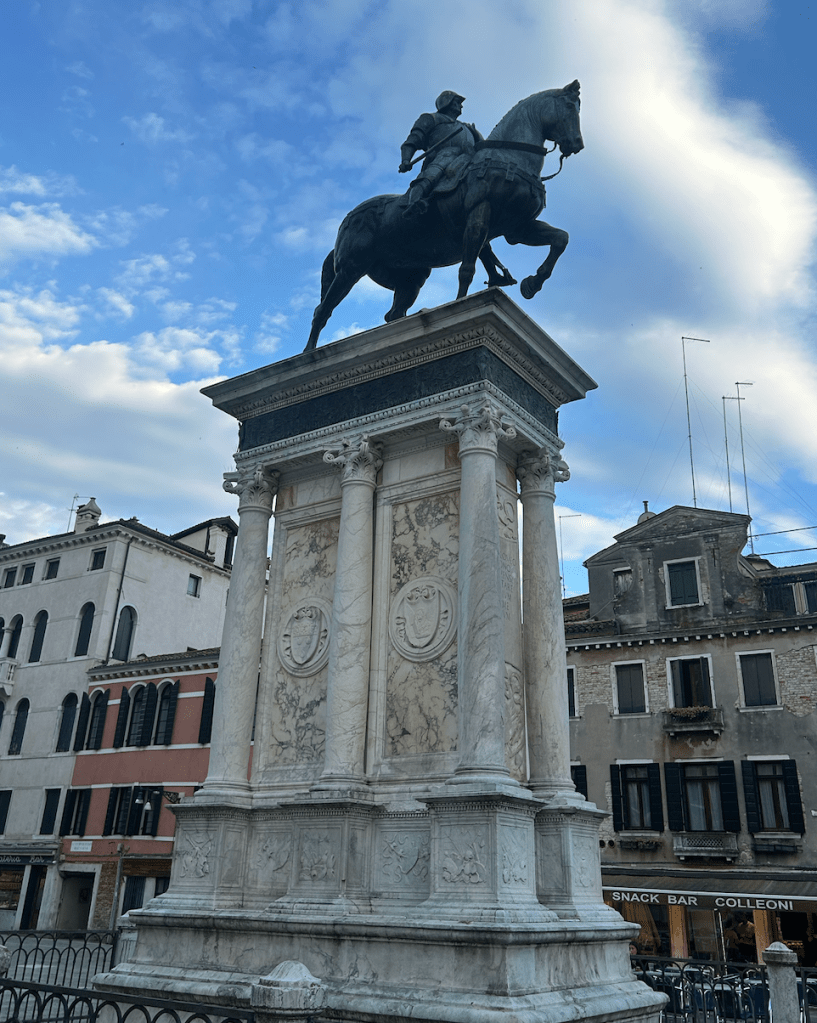

When you first walk into the campo, the uneven cobblestone that paves the campo feel smooth under you after being worn down after years of traversing feet. As you cross the bridge to enter the campo, an ornate marble façade belonging to a hospital, adjacent the earthy red brick of an old church, and the open plaza invite you in. At the heart of the plaza, a towering metal horse statue upon an intricate marble pedestal and the sound of the flowing canal in front of it.

The famous campo is home to a horse statue with unsupported hoof up in the air, which is evidence of engineering marvels performed at the time of construction. The residential buildings that flank the canal stand tall displaying a sea of orange and red hues, giving contrast to the grey and marble presentation that dominates the campo. The mix of Renaissance and Baroque façades gives this campo a personality, attracting all those who walk past.

The chatter of travelers and locals alike brings the square to life, as people dine in the osterias lining the campo and church bells ring. The quiet humming of the water providing background noise for the buzzing scene, as people mingle and connect on the shining cobblestone. The saints and Venetian lions lining the rooftops observe as the days go by.

When we first think of Venice, we paint a mental image of swirling canals, black gondolas, stone bridges, and imposing architecture; we picture a city ruled by water. For a city compressed along the canals, there are large empty spaces called campi tucked away in the tangled streets.

A “campo” is a large or open public space, which are only found in Venice. Historically, these areas were covered by field and swamp before being paved, hence the name “campo”, which means “field”. These Venetian Campi take you back in time as you walk through them, displaying centuries of varying architectural styles ranging from Venetian Gothic to Medieval and beyond.

Campo Santi Giovanni e Paolo (also known as San Zanipolo) is one of the most important and historical public campi in Venice. It has roots dating all the way back to 1246, when the Dominican Order was allowed to construct a church in the square. The land was originally swamp, and so it was filled and developed to the square that it is now.

Historically, campo has been the setting for public gatherings, markets, celebrations, and serve as a connecting point for the community. Now, it still serves as an important gathering place for locals, but it is also now has a bigger emphasis as a popular spot for millions of tourists on their way throughout Venice.

Geertz wrote in his Deep Play: notes on the Balinese cockfight that, “[Bali’s] mythology, art, ritual, social organization, patterns of child rearing, forms of law, even styles of trance, have all been microscopically examined for traces of that elusive substance Jane Belo called the ‘The Balinese Temper’” (59). Similar to Geertz’s interpretation of “the Balinese Temper” as insight into the rich Balinese culture, Venetian campi can also be treated as such. The campo shows the history, values, routines, and struggles of Venetian life. Ranging from how locals gather at sunset to share meals and gossips, to the story told by the imposing architecture, Venetian campi display the mix of spectacles, rituals, and community characteristic of Venetian life.

Architectural Elements

The Hospital

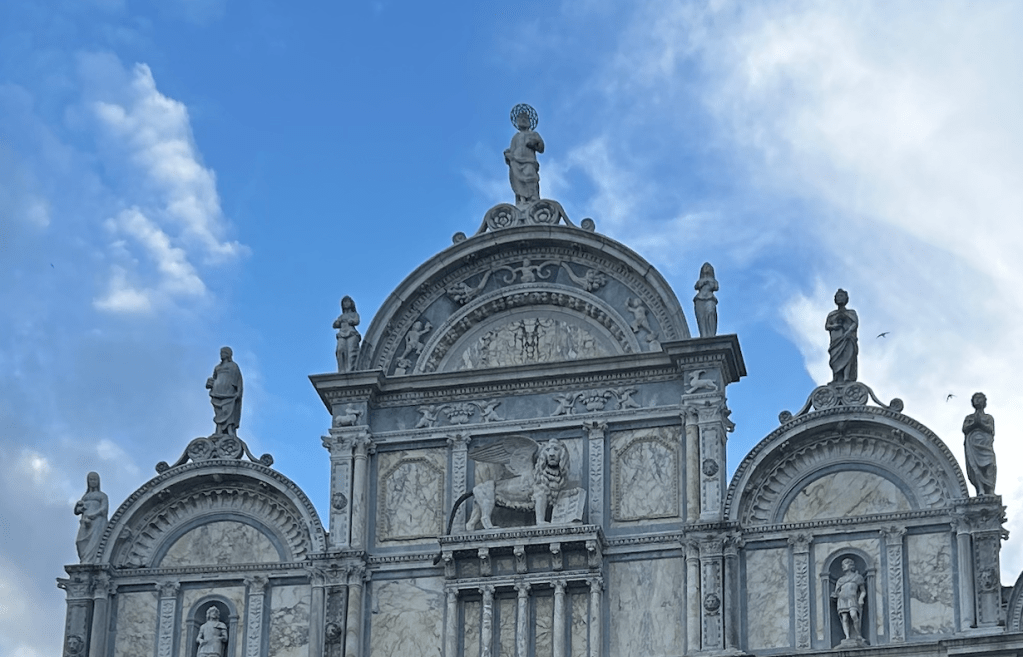

This makes sense since originally, the site was home to the Scuola Grande di San Marco, a “confraternity” established in 1260, which was influential in religious, social, and artistic aspects. After a devastating fire in 1485, the building was reconstructed in the Renaissance style under the guidance of architects Pietro Lombardo and Mauro Codussi, resulting in the marble façade that we see today.

The primary style of the hospital is Venetian Renaissance, with influence from the late Gothic period. Its Renaissance features include symmetry, classical columns and pilasters, marble cladding, round arches, sculptures representing religious figures and daily life, rounded arches, arch motifs, and has an emphasis on clean geometric lines. As well as stilted arches, segmental pediments, rustication, and voltes. Venetian Gothic is shown on the outside of this building through the pediments, pilasters, and circular windows/elements on the exterior. This also includes decorative tracery which is seen in the stone lacework in the windows and vertical emphasis.

The religious designs decorating the hospital align with the time period of the Venetian gothic when it was first built since the shift away from religion observed in the Renaissance had not yet happened. This is especially relevant concerning the placement of the Venetian lion in relation to religious statues at the top of the church; the statue of a St. Mark the Evangelist was specifically placed higher than the Venetian lion to show allyship to the Catholic Church.

The Basilica dei Santi Giovanni e Paolo

The building dominating the campo is the church dedicated to Saint Giovanni and Saint Paolo. The basilica was constructed during the 13th and 14th centuries by the Dominicans. It houses rich art and cultural heritage, and has been preserved due to a thorough restoration in the middle of the 20th Century.

This basilica is located next to the right of the hospital. The primary architecture style of the church is Venetian Gothic. This is exemplified through the pointed arches in doorways, large circular windows, cusps, blind arcades, lancet windows, and relief ornaments above the main entrance.

The sides of the basilica exemplify lanterns, etc. While the cross adorning the roof may not be the Greek cross typically associated with Venetian Gothic, the layout the church itself does reflect the structure of the cross.

Examples of circular windows, symmetry, cusps (white trim along the furthermost top of the building), and pinnacle-esque elements of Venetian Gothic.

The front façade of the basilica has pointed arches indicative of Gothic architecture, and the smooth marble columns reminisce the classical revival of the Renaissance period. The central element of the façade displays three saints– St. Peter the Martyr on the left, St. Dominic in the center, and St. Thomas Aquinas on the right.

The Statue & square

Another monument amidst the square that is worth admiration is the massive statue of Bartolomeo Colleoni, designed by Andrea del Verrocchio (Leonardo da Vinci’s teacher). This equestrian statue was done in 1496, making it a masterwork of the Renaissance. This civic monument is important for many reasons, some of them being that it was one of the first fully Renaissance statues because of its realism, anatomical precision, and dynamic posing. It is also symbolic of Venice’s civic pride and military strength. It was a symbol of state power and integrity in service of the Venetian people.

The floor itself spans 4,500-5,000 sq meters, and is paved primarily with traditional Venetian trachyte stone, believed to have been sourced near Padua. Large, rectangular slabs of rock were arranged in an irregular grid pattern, covering what was once swampland. This paving is a reflection of the practical necessity for open areas in such a densely packed city.

The Residential Buildings

The residential buildings surrounding the square show traditional Venetian residential architecture. This style is characterized by tall, slim, rectangular buildings with decorations on the front facing the center of the campo. Venetian Gothic continues to be an influence in this style, particular buildings even showing trifora windows, some with pointed arches which are typical of Venetian Gothic. The smooth stucco walls, shutters, and balconies are more of the Renaissance style, with some elements specific to Venice.

More than just stone: Functions of the Campo

Historically, campo has been the setting for public gatherings, markets, celebrations, and cultural events, especially Carnival. Now, it still serves as an important gathering place for locals, but it is also now has a bigger emphasis as a popular spot for millions of tourists on their way throughout Venice.

The presence of the church allows for the campo to be a spiritual center for the neighborhood. Religious festivals, public sermons, and activities put on by the church have taken place here. This allowed for the connecting of spiritual life with daily life, reinforcing the grasp of the church on Venetian citizens. Furthermore, the campo served as a marketplace as well; food, wood, textiles, fish, etc. were all sold here. It helped support the economy and the trading of goods from various places allowed for the spread of ideas and information. Since the campo served as a rendezvous point for so many activities, it had/has the ability to connect locals and tourists alike. The campo continues to serve as a sort of neutral communal space, where neighborhood identity and social connections were defined.

Each of these functions influenced and supported the others; spiritual events brought people together, who then shared information, traded goods, etc. all in the same square. These campi can be considered heterotopias of sorts. As Foucault mentioned in Of Other Spaces when discussing how cemeteries are heterotopias, “It is a space that is however connected with all the sites of the city state or society or village, etc., since every individual, each family has relatives in the cemetery” (25).

Though he is not discussing campi, it still applies because they are a melting pot of varying ideas and social orders. They juxtapose incompatible spaces such as churches, markets, civic events, and leisurely activities such as theater or gatherings in a single space. Furthermore, they also display different moments in time through the architecture and the transformation of the functions of the space can be shown; it is a place where daily life and values are constantly reimagined.

As a result of this exercise, I have gained a new appreciation for Venice as a tourist through being able to understand the layout of the city more. I now realize that campi are more than just open spaces, they are the heart of Venetian life. In areas like these, daily life, history, and local culture collide. As a tourist, experiencing these areas has offered me an appreciation of Venice beyond the superficial sights. I have also learned that every single campi has its own history, and through the varying history, the evolution of community and society can be observed.

Being in a campi allowed me to observe Venetian culture through hearing the italian language spoken and the music in the air; through watching elderly Venetians and teenagers socialize alike in the campi; and through watching others just go about their daily routines. Simply watching human interaction has painted an image of Venice that cannot be attained in museums.