EATaly: Culinary Experiences in Italy

What is the value and logic of Italian cuisine compared to postmodern American approach?

When one thinks of Italian food, things like pizza, pasta, tiramisu, burrata, etc. probably come to mind. While those foods may be very prevalent in Italian culture because of their flavor profile and iconic standing, they are also popular because of their deep cultural significance.

When comparing Italian cuisine to the postmodern American approach to food, we uncover two very different logics and sets of values. Italian food prioritizes tradition, quality ingredients, and regional identity, reflecting a culture that values time, craftsmanship, and communal connection. Postmodern American cuisine, on the other hand, often emphasizes efficiency and experimentation (perhaps through fast food culture and experimental dining). My time in has Italy allowed me to experience firsthand how food can preserve a way of life, while American habits seem to reflect a culture of speed and disconnection from origins.

Italian culture emphasizes enjoying food, fostering connections, and taking your time. The logic behind Italian cuisine is that by conserving traditional culinary practices, like making pasta by hand and savoring meals, tradition, technique, and cultural identity can be preserved.

Robert S. Nelson, in Visuality Before and Beyond the Renaissance, discusses how our perceptions are never neutral, writing that “every viewer belongs to a society and subscribes in varying degrees to the bodily conventions and practices of that society” (8). Though his focus is art history, the insight applies also to food culture. In Italy, dining is influenced by a set of bodily rituals (waiting patiently for food, lingering at the table, using one’s hands to make pasta)that reflect a cultural script very different from the American norm.

These practices are not just about food but about enacting a social and historical identity through the body itself. My own unease with the slower pace at first revealed how deeply American dining habits (speed, efficiency, productivity) have shaped even my physical expectations of a meal.

Italian cuisine is long standing, meaning it has not changed much over time so as to conserve that sense of novelty and tradition. Beyond the food itself, the value placed on these practices reflects the deeper importance of community and heritage in Italian life.

For example, In Italian restaurants, typically there are multiple courses: antipasto (appetizer), primo (first course, typically pasta), secondo (main course, like meat/fish), contorno (side dishes like vegetables), and finally, dolce (dessert). Dinner typically lasts more than 2 hours because the time is taken to appreciate the food, to enjoy the presence of others, and to enjoy themselves. When a space is created for appreciation of cultural practices to take place, a culture thrives and it lives on.

In Art and Illusion, E.H. Gombrich notes that we tend to “register our experience in terms of the known,” which poses a challenge for artists confronting something unfamiliar (168). This idea also resonates with how cultural practices like Italian dining are misinterpreted. During my first meals in Italy, I caught myself framing the long dinners and multiple courses as simply “old-fashioned” or “relaxed”; which was my attempt to understand the routine from an American perspective. But Gombrich’s point reminds us that such interpretations can obscure the deeper logic of unfamiliar practices. What I had initially dismissed as a slower way of eating was, in fact, a deliberate preservation of memory, family, and identity through the motions of a shared meal. Gombrich pushes us to pause and truly perceive rather than fit everything into a familiar mold.

Additionally, in the U.S. food is often subordinated to the logic of productivity. Meals are compressed into lunch breaks or eaten in cars; the body becomes a vehicle for sustenance rather than an active participant. This is not merely a matter of convenience; it reflects a postmodern condition in which time is fragmented, and tradition is displaced by novelty.

The logic found behind American cuisine today highlights speed, efficiency, and experimentation. In American dining, tables are turned quickly at restaurants with the average time spent dining ranging from 40-60min, fast food and take out are popular options, and many Americans find themselves rushing through their meals.

The values that are extension of this logic include individualism, convenience, and diversity. By contrast, Italian meals reclaim time as something communal and sacred. The extended meal structure is not just culinary tradition, but a social script. Eating becomes an act of presence, one that resists conformity to postmodernism. In this sense, Italian cuisine functions against American postmodernism: it asks us not just to eat, but to dwell and live in the moment.

the image above portrays a popular American breakfast, Avocado toast. American breakfasts vary from person to person and depend on the region.

Fast food is a culture within itself, but unlike Italian culture it does not preserve heritage. This postmodern approach to dining encourages a sense of individuality and the shift away from tradition. However, this is not all bad as it also embraces experimentation, diversity, and personalization, which is part of the postmodern essence.

The logic and values of the pre-modern Italian approach to cuisine offer meaningful lessons on how food can preserve culture, foster community, and encourage a slower, more intentional way of life. It serves as a gentle reminder to pause, savor good meals, and connect with one another. In contrast, the postmodern American approach to dining reflects a different set of values centered on speed, individualism, and innovation. While these values may seem at odds with traditional practices, they are shaped by a broader cultural evolution, influenced by both Renaissance ideals of personal freedom and postmodern trends toward experimentation and diversity.

Culinary, Cultural Experiences, and Lessons Learned

My time in Italy has allowed me to experience authentic homemade gnocchi, pasta, preparing pizza, and a typical meal in a restaurant. Additionally, I was granted the privilege of having dinner with an Italian family in their home.

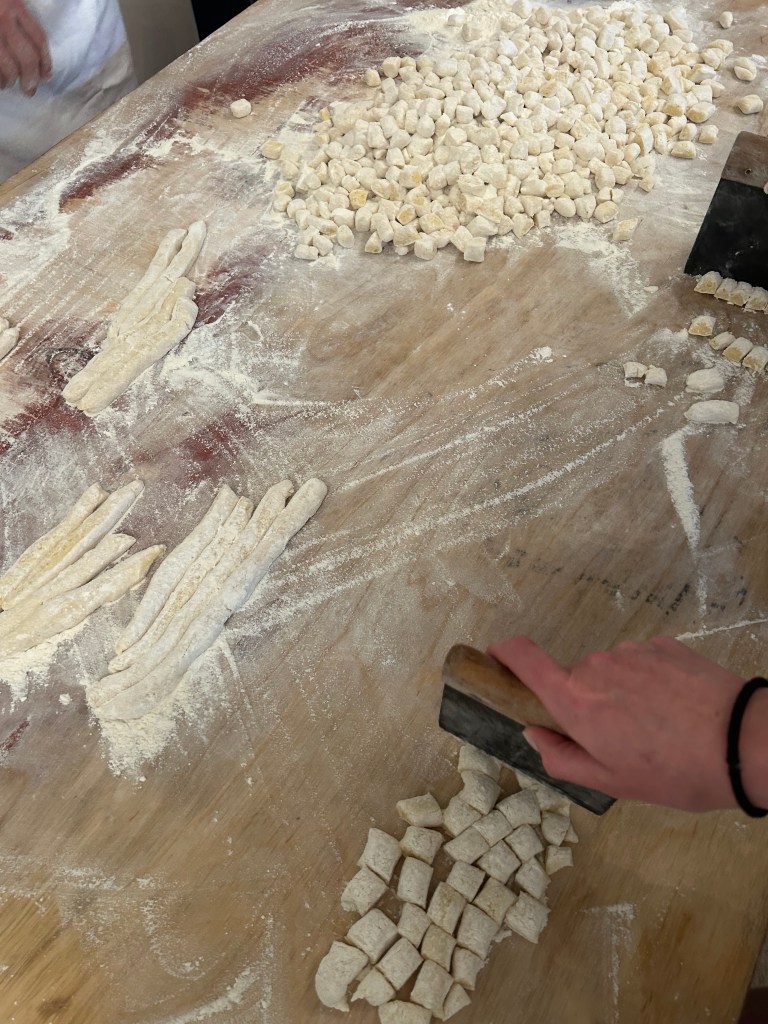

My group and I had the privilege to watch pasta/gnocchi making in Castelcucco, Italy. Lucca, the instructor & owner of the restaurant we were in, had inherited the restaurant from his parents who had taught him the art of making pasta, much like his parents before him.

He taught us that when making pasta, there are no set measurements and it is all about how the dough feels in your hands (the texture, the color, the bounciness of the dough when you touch it). It is a very laborious process, as measuring the flour, mixing the dough, letting it rest, rolling it and cutting it, is all done by hand. His improvisational approach to pasta-making contrasts the mechanized and quantitative food preparation in the United States. Him doing this suggests an embodied knowledge (knowing and learning through doing), which resists the rationalization and standardization status quo of post-modern food culture.

Lucca and his family are guardians of their Italy’s culture, as they work hard to ensure that the art of preparing food is not lost. While it may seem easy, it takes a tremendous amount of practice and skill to perfect the craft, which is why many people have turned to packaged foods.

He brought up the term “cucina povera” , which directly translates to “poor kitchen”. This refers to a style of cooking that stemmed from the rural and working-class communities of Italy, that utilizes simple, inexpensive ingredients. Examples of this include pasta e fagioli (pasta & beans), polenta (cornmeal porridge), frittata (egg dish with vegetables or pasta), etc. The cultural significance behind this is that it is about honoring tradition and the creativity of those who came before us. Today, it serves as a reminder of the humble roots that gave way to the delicious, heartfelt Italian cuisine we love.

Another experience I have enjoyed is dining in Italian restaurants. Living in the United States, it was quite a culture shock that when you sit down to dine, the waiter doesn’t check on you for at least 30min (maybe even more than 1hr), and you are expected to stay there for a very long time. I enjoyed this because it is a great way to experience the aspect of Italian culture that involves appreciating the food and basking in the company of your dining partners.

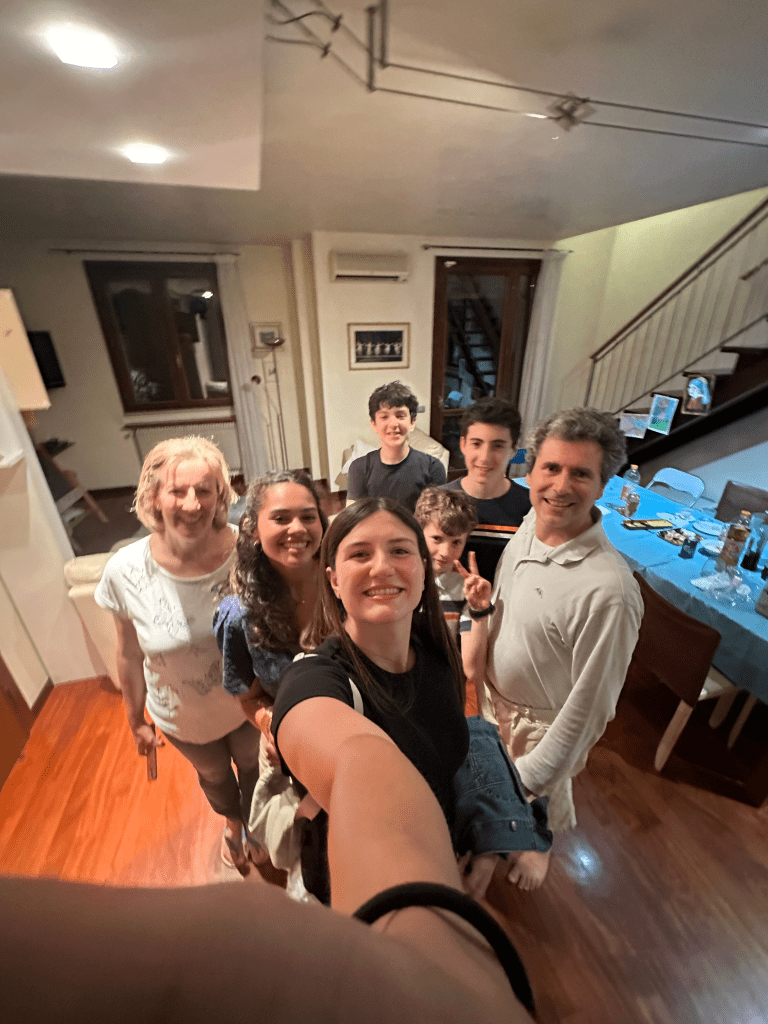

Apart from this, a highlight of my time here has been dining with an Italian family in their home. They were incredibly kind enough to let my peer and I join them for dinner. Their home was so warm and inviting, and as we broke bread, I got an insight into an average dinner in an Italian home. The meal itself wasn’t as extensive as one in a restaurant would be. It was quite simple, but we stayed at the table after having an espresso and a digestivo. We talked for hours, making connections within our distinct cultures and discussing our lives; in this moment, it became clear how the Italians use dining as a vehicle to fortify their values of community.

Kneading dough in a quiet kitchen in Castelcucco or sipping espresso after dinner with an Italian family were not just pleasant experiences—they were lessons in a different way of being. In these moments, I came to see how food operates as a cultural script, one that is written on the body as much as the plate.

While postmodern American dining favors fragmentation (quick meals, individualized orders, and the illusion of choice) Italian cuisine insists on continuity. It binds the consumer to history, to family, to place. In doing so, it resists the erosion of meaning that often accompanies convenience culture. Through the lens of Nelson’s and Gombrich’s theories, we begin to see food not just as sustenance or tradition, but as visuality, memory, and embodied knowledge.

Italy taught me that to eat is to remember, to belong, and above all, to be present. That is a lesson worth bringing home.